Distilling complex ideas and our warped time perception during the pandemic

Friday Brainstorm S2 E5 🧠

Hi friends,

Happy New Years! Welcome to the first Friday Brainstorm newsletter of 2021.

It’s hard to believe that we’re hitting on 20 issues of this newsletter since March. There’s no time to reminisce though, I have so much planned for this upcoming year.

Most notably, Friday Brainstorm has been a one-way street for far too long. I’m going to be starting a learning club to bring together the community of readers around our shared interests in neuroscience, learning, metacognition, or whatever it might be. I’m really excited about the future of peer-to-peer learning experiences and thought that this would be a great way to add a participatory element to this newsletter.

In the meantime, here’s what in store today:

parsing and transmitting complex ideas 💡

warped time perception in the pandemic ⏱️

(podcast) transforming your relationship with digital tech 💻

Let’s get into it.

On deconstructing complex ideas 💡

Tim Urban, and his Wait But Why blog, has been a huge inspiration to me both as a writer and as a curious person. He’s probably appeared in this newsletter more than anyone else — on relationships, on politics, and on the future of neurotechnology.

In a fascinating 2018 interview, Tim shares how he distills and presents complex ideas so they’re rich and resonant for others. He introduces his personal taxonomy of complexity and deconstructs his process for unravelling the different types.

“When thinking of an idea that’s hard to understand, it’s tempting to think of complexity in a singular way. Instead consider it in three distinct forms: complexity as gathering, complexity as dusting, and complexity as pattern-matching.”

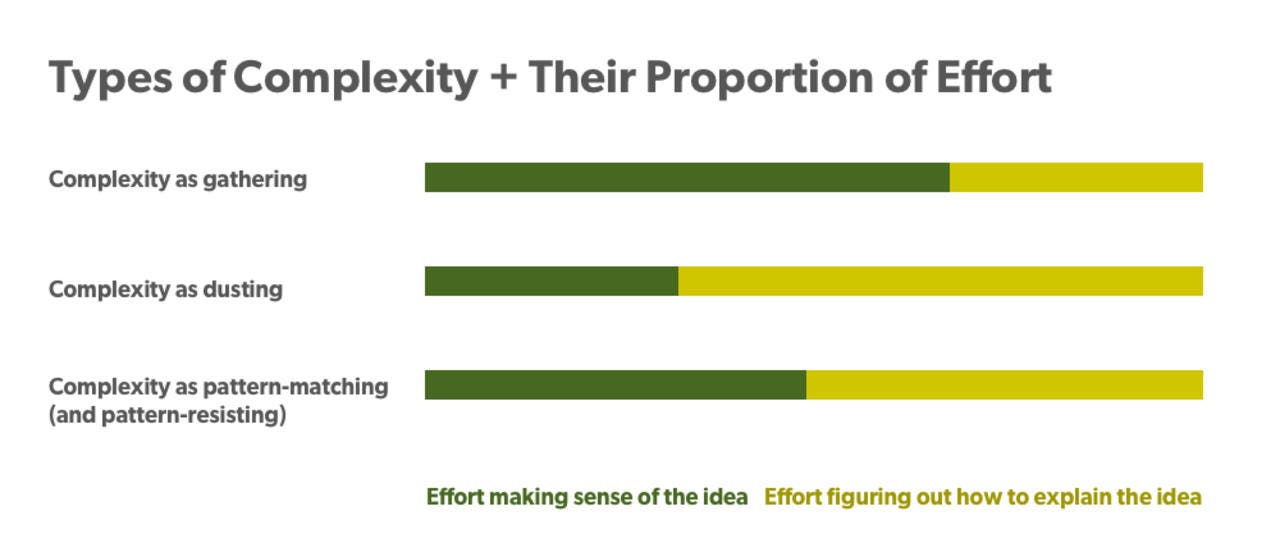

What’s different is the type and proportion of effort needed to crack the case — knowing that ratio can help you better tackle complex ideas.

1. Complexity as gathering

These are ideas that aren’t particularly difficult to explain, but require a lot of up-front research and learning to make sense of.

It takes Urban an average of 160 hours to learn everything he needs to learn about a topic to write a post. Urban knows he’s lucky if a reader will spend two hours reading his post, so his challenge is to present complex topics in a way that readers can learn 80x faster than he did.

The key skill is the ability to find the relevant material and to synthesize it in a concise and approachable way. The challenge is to guide your readers through the information and engage them well enough that they can still explain the idea two weeks later.

An example is Urban’s Neuralink post, Elon Musk’s brain-computer interface venture.

2. Complexity as dusting

These are ideas that are more revealed than learned. It’s about finding simple yet powerful concepts that aren’t obvious at first glance. A great example is Urban’s cook versus chef concept.

The challenge here is to explain the idea in a way that people not only understand it, but know how to apply it in different contexts. I love this quote from Tim:

If you’ve explained it, you've just done step one of 20. The next 19 steps are the hard part, which is getting to a place where people deeply internalize the concept in the different ways that it manifests in life — and that they have words that they can assign to it and visuals so they can really envision the concept. To me, it's getting that concept deep into someone's psyche — not just into their understanding, but into their intuition.

3. Complexity as pattern-matching (and pattern-resisting)

These are ideas that share characteristics with both the first two types of complexity. They require intensive up-front research and learning as well as looking out for the underlying patterns that others don’t notice.

The challenge is “assigning each new bit of information to a pattern and then — and only then — deciding if that pattern should be included or resisted”. In other words, this class of complexity often comes with preset patterns accepted as the status quo. It’s important to start from first principles and move past the usual approach.

The best example is Urban’s The Story of Us. He spent three years working on a new metaphorical language we can use to think and talk about our societies and its people.

—

For each type of complexity, there’s a different ratio of effort needed to make sense of the idea versus figuring out how to explain the idea.

In the rest of the article, Tim expands on the questions to ask and tactics to consider as you’re thinking through how to explain a complex idea. Really fantastic read!

Warped time perception during the pandemic ⏱️

Recently, I came across a Vox article about how our relationship with time was altered by the pandemic. To cap off the year, it feels fitting to reflect on this theme.

The pandemic has brought two types of changes affecting our perception of time:

we’ve lost our usual markers of time to divide up days, weeks, and months

we’ve lost our sense of the future due to the uncertainty of when it will end

Let’s explore what psychological effects each of these might have on memory and other cognitive functions.

Loss of usual markers of time

Before the pandemic, many of us had routines that would segment our lives.

“We wake up, take the kids to school, commute to work, take lunch breaks, go to the gym, have dinners out. Now, though, any activities we once might have participated in outside the home have been abruptly removed, and we’ve lost the sense of time these seemingly mundane markers once provided.”

Without these markers, thinking back to the past 9 months can feel like a blur even though each individual day may have felt torturously long. It turns out that our retrospective perception of time, or the subjective experience of looking back, is closely related to our memory.

This isn’t intuitive, but the evolutionary purpose of memory is predict the future. It allow us to draw on past events, experiences and emotions to construct plausible scenarios of future events and act accordingly to increase our chances of survival.

To bring up a silly example - we know not to touch a hot stove because we’ve likely made the mistake in the past and our brains cemented the memory to dissuade us from doing it again. Whether or not to capture a long-term memory depends on its usefulness to us, whether physically or socially.

Since most people didn’t have many novel experiences this year, our brains have less useful information to represent in memory relative to past years. As a result, time seems to pass quickly in retrospect. Hopefully you took a few photos to fill in the gaps.

Loss of our sense of future

Perhaps more disorienting has been the uncertainty around the future. To reiterate, time perception supports the brain’s most important function: predicting the future.

“Covid-19, and its resulting effect on our lives, has stifled this instinct. Even thinking about the future conjures only a strange, fuzzy block because we know neither when this will end nor how different our world will look when it does.”

A major source of stress for a lot of people is not being able to plan ahead and reduce the ambiguity of what the future might hold for them. It’s natural to want to feel in control and have your life figured out; it’s one of our most inherent skills and desires.

An interesting parallel is the experience of schizophrenic patients, who commonly report a disturbance in the continuity of temporal experience. Time seems to stand still for them, and with that, it feels like the “self” is stuck in the present with all future perspective vanishing.

This might be hard to wrap your head around, but “the consciousness of time and consciousness of self co-create each other to construct our experience of who we are.” These patients cannot integrate the past, present, and future and so their continuity of self is shattered.

I’m not trying to say that our experiences during the pandemic compare to that of schizophrenic patients, but we could better understand the existential dread that hangs over us through this lens. Our experience of self relies in part of our ability to anticipate the future, which is disrupted by a high degree of uncertainty. What we’re left with is the past and present, which is highly unnerving to our brains. This leads to the subjective experience of time passing very slowly in the moment.

—

Curious for more? I’ve previously written about time — how our time perception is linked with our experience of self and why time feels faster with every year.

Transforming your relationship with technology 💻

In episode 3 of the Mind Gym podcast, we explore strategies for hacking back against social media, outlining specific techniques developed by experts for living a more intentional, distraction-free life by transforming your relationship with technology.

Check it out 👇

—

In the podcast, we draw on concepts from Cal Newport’s Digital Minimalism. Back in 2019, I wrote an article where I summarized the most important ideas and contrasted them with Nir Eyal’s Indistractible — which approaches the same problem differently.

Here’s a snippet from the article:

A more subtle commonality between the two authors is the importance of committing to what Nir calls an identity pact, or a commitment to a self-image. The idea is that you can prevent distraction by acting in line with your identity, which has a significant impact on our behavior.

Nir overtly advocates for “becoming a noun”, with the noun being indistractable, which also happens to be the title of the book. Cal is a bit more subtle about it, dispersing throughout the book what it means to be a digital minimalist. These are powerful psychological appeals that attempt to help the reader reframe how they think about themselves.

If you’re curious, go ahead and read the whole thing.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this issue of Friday Brainstorm! What got you thinking? Anything to add? Let me know by replying to this email.

—Shamay